Remembering Roger Brown: A UD Basketball Player Who Was Wrongfully Accused of Sports Fixing

Griffin Quinn

Print Editor-in-Chief

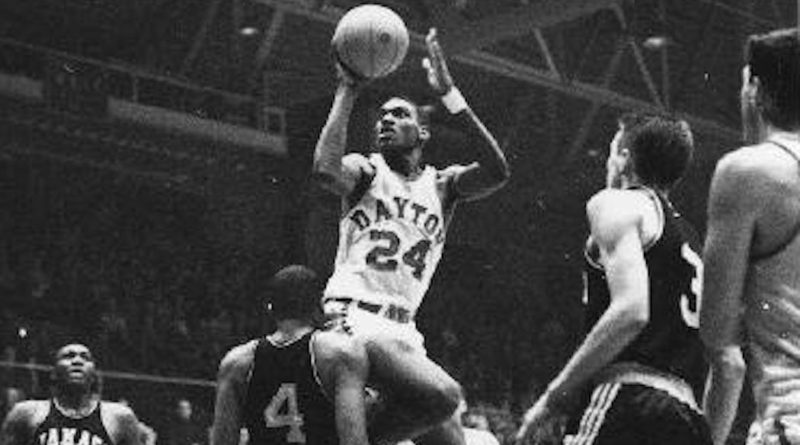

Roger Brown (24) in uniform for the Dayton Flyers. He only played one season before being banned from the NCAA on a charge of sports fixing with minimal evidence. Courtesy of the University of Dayton

College basketball season is in full swing, and the Dayton Flyers look as good as ever. With stars returning to a roster flooded with newly added transfer talent, the sky is the limit for this year’s men’s basketball team. As fans applaud the wildly impressive athletes of the present, it is time that we at Flyer News pay our dues to arguably one of the greatest to have ever played in the Flyer red and blue: Roger Brown.

A Kid From Brooklyn

Born on May 22, 1942, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, Brooklyn was Brown’s home. It is in this famed borough of New York City that the 6-foot-5 guard would develop his basketball talent. It was in Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden where, in the semifinals of the 1960 New York City Public Schools Athletic League tournament, Brown showed that he was the best player in his hometown of his time to call Brooklyn home.

Brown was the star for Wingate High School. His team was tasked with going head-to-head with a Boys High squad that featured fellow Brooklyn star Connie “The Hawk” Hawkins in the semifinal. It was a clash of two titans – at least for three quarters. That is when a frustrated Hawkins fouled out of the contest. He was unable to contain the smooth-gliding and high-scoring Brown who finished the game with 37 points.

Hawkins’ Boys High would ultimately prevail and advance to the 1960 final, but Brown had showcased his talent in The Garden.

Both Hawkins and Brown graduated from their respective high schools following that season and both headed west to distinguished NCAA Div. I basketball programs: Hawkins, to Iowa, and Brown, to Dayton.

Flying in (and out of) “The Fieldhouse”

When Roger Brown arrived to the campus distinguished by a sky-blue chapel in the fall of 1960, the Dayton men’s basketball team played its game in “The Fieldhouse,” now known as the Frericks Center. Brown joined a talented freshman Dayton basketball roster. Many believed that he was set to be the next NCAA sensation.

Those collegiate expectations were short-lived.

After a successful freshman campaign, Brown returned to New York to appear in court for a car accident he was involved in prior to his time at UD. The car had been owned by a man by the name of Jack Molinas.

Molinas, a Columbia University graduate, was selected third overall by the Fort Wayne Pistons in the 1953 NBA draft. After playing in just 32 games for the Pistons, Wayne was banned from the NBA as he had been discovered to have been placing wagers on Pistons games. Eight years later, Molinas – along with known New York gambler Joe Hacken – was at the center of the 1961 point-shaving scandal in which 37 players from 22 colleges had allegedly been involved in the gambling ring.

Among the most notable names mentioned in the point-shaving investigations were Brooklyn stars Connie Hawkins and Roger Brown.

Back in New York, Hacken and Molinas were frequently spotted at local basketball courts, making connections with neighborhood stars. Authorities believed that Brown, in the summer prior to his start at UD, had accepted money from the two men in exchange for introducing them to other local athletes. Once at UD, Brown had no connection to Hacken or Molinas. His previous association was only brought up during the court appearance for the car accident.

During his time at UD, there was no evidence that Brown had shaved points in a game. Nevertheless, the NCAA was embarrassed that such a massive scandal had taken place and they were swift to punish anyone they could.

Brown was banned from the NCAA and, subsequently, the University of Dayton.

While the NCAA was swift with its conviction, UD was passive. In a past interview with Dayton Daily News, Bing Davis – a former teammate of Brown’s and a local artist – said that “Dayton pretty much cut the cord on [Brown]… It cast him adrift.”

The university failed to defend its student-athlete from the all-powerful NCAA, and there is little evidence to show the university’s behavior was warranted. Minimal documentation is available from the university’s decision to remove Brown from campus. There is little known about what was said behind closed doors in the conversations that determined Brown’s fate.

Teresa Saxton, a full-time faculty member and lecturer who had done research on Brown out of personal curiosity, had asked many people about Brown’s story.

“You don’t find information on Brown at the University of Dayton very easily,” Saxton said. “Looking through the archives, you can see articles on Brown in games from the year he was here, but there’s nothing else.”

When asking individuals about Brown’s story, Saxton noted that their responses often began with the phrase “From what I understand…”

After just one year at UD, Brown had been cast away on account of being found guilty by association. And, just as he had disappeared from campus, so did the evidence of his story.

New Associations

After being banned from the NCAA and removed from the University of Dayton, Brown was blacklisted from the National Basketball Association.

Brown dismayingly returned to Brooklyn. Shortly thereafter, he made his way back to Dayton where he joined the workforce and began playing in the city’s industrial basketball league.

In the summer of 1967, the Indiana Pacers – a member of the newly-formed American Basketball Association – made Brown the first athlete signed to play for their organization. At that time, 25-year-old Brown had been working a night shift at the Dayton General Motors factory.

Half a decade removed from his time at UD, Brown made a name for himself in the ABA.

In his eight-year ABA career, Brown played in 605 games and was the first ABA player to reach the 10,000 point threshold averaging 17.4 per game while also having averaged 6.2 rebounds and 3.4 assists per contest. He led the Pacers to three league championships in the early 70s.

In his final seasons, the NBA removed their ban on Brown; however, he chose to remain loyal to the Pacers organization as it had been the first professional team to give him a chance.

Brown played his last game for the Pacers in 1975. His no. 35 jersey is one of four numbers to be retired by the Indiana Pacers who had joined the NBA following the 1976 merger.

Following his playing days, Brown served on the Indianapolis City Council.

In 1997, at age 54, Roger William Brown passed away. He left behind his brother, two sisters, three sons, four daughters and six grandchildren.

Many consider Brown to have been one of the greatest ABA players and some say that, if given the chance to prove himself in the NBA, Brown could be one of the top 50 basketball players of all time. He was one of seven players unanimously selected to the ABA All-Time Team in 1997 and, in September 2013, was one of five direct inductees into the Naismith Hall of Fame.

“Truth and Reconciliation”

This fall, Roger Brown’s name returned to campus.

On Sept. 27, 2019, the University announced the beginning of a Roger Brown Residency in Social Justice, Writing, and Sport. This residency, scheduled to become an annual event, will feature distinguished writers who explore social justice in athletics and literature.

“I think one of the reasons they made this residency is to give Roger Brown a footprint on campus,” Saxton said. “Because his name hasn’t been on campus until the residency.”

The inaugural writer in residence was Wil Haygood, author of “Tigerland,” “The Butler” and “Showdown,” among others. Haygood visited campus from Nov. 5-7 to discuss Roger Brown and the university.

“Roger Brown was just a young black kid in America who was trying to find his way,” Haygood said. “There is no doubt that he was extremely shaken up from the decision by the university… He had to feel alone in an extreme way.”

In his Nov. 6 address, Haygood – a man of many stories – shared his experience witnessing Nelson Mandela take his first free steps after being imprisoned for 27 years. Relating this experience in South Africa to the story of Roger Brown, Haygood discussed Mandela and the idea of “truth and reconciliation” which stems from the truth and reconciliation commission, a committee tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by an institution with the hope of resolving conflict left over from the past. Under Mandela’s leadership, South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commission was established in 1995.

Reflecting on the story of Roger Brown, Haygood noted that, in many ways, the establishment of a residency at the University is an acknowledgment of the institution’s past wrongdoings and is a step towards reconciling them.

“We often, in life, find figures who can teach us. And, when an institution of higher learning finds a figure who has suffered pain at that very institution and then that institution does something as profound as naming a residency after him, then that is something to honor,” Haygood said.

“Sports and sports figures have always played a very crucial part in telling the narrative of this country. This Roger Brown saga, which has been hidden for so long, could have very well stayed hidden,” Haygood said. “It is a wonderful testimony to the school to have gone back into the past and pointed out the Roger Brown story so that we all might continue to learn from it.”

Writing to Remember

In the past few years, we at Flyer News have been working to digitize our print archives. In the writing of this article, nothing was found in our archives pertaining to the dismissal of Roger Brown from the university.

This is the first Flyer News article to mention Brown’s departure from campus.

As a University of Dayton student and someone who has followed Dayton basketball for quite some time, I had not even heard of Roger Brown until the announcement of his residency this fall. The lack of shared knowledge about Brown is an injustice in itself.

That said, the recognition of this injustice and the effort to make amends for it, from leaders at the University of Dayton is something that we, as an institution of higher learning, should be proud of.

We cannot undo the past, but it is important that we acknowledge it, share it and learn from it so that we can avoid making the same mistakes in the future.

For more sports news like Flyer News on Facebook and follow us on Twitter (@FlyerNews & @FlyerNewsSports) and Instagram (@flyernews)

For questions about this article, please contact the writer at quinng2@udayton.edu