Looking back to move forward: 20 years after the Dayton Peace Accords

By: Amanda Dee – Online Editor-in-Chief

Igor Crnadak was the first one on radio waves to say it: The war was over.

“After almost four years,” Crnadak remembered, “… the bloodshed and the kills and the terror of the war came to an end.”

Hundreds and thousands of people called each other’s homes. Hundreds and thousands of rifles shot into the sky. The war was over.

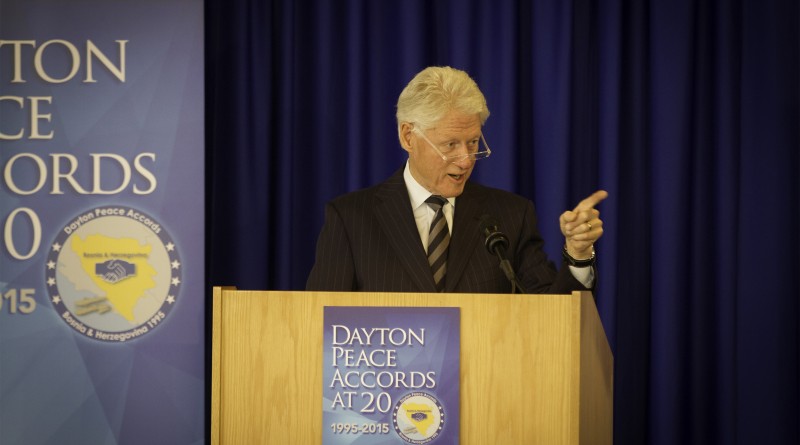

Twenty years later, Crnadak was standing at a podium in a suit and tie, the minister of foreign affairs for Bosnia- Herzegovina. And he had another announcement: It was time for the Dayton Peace Accords at 20 keynote speaker, former United States President Bill Clinton.

To a sold-out University of Dayton River Campus ballroom Nov. 19, Clinton stressed the importance of Bosnia and the Dayton Peace Accords today.

“We’re back here to celebrate one victory and what has turned out to be an ongoing contest across the globe between violence and negotiation, cooperation and conflict, inclusion and winner-take-all politics—and the whole question of human identity,” Clinton said. “Whether we can only celebrate our diversity in an interdependent world when we recognize whether our common humanity matters more or whether we can only be faithful to our diversity if we’re willing to kill everybody who disagrees with us.”

The cracks of the Balkans, a peninsula in Southeast Europe, widened after the 1991 collapse of the Yugoslavian communist regime that once dominated the region. The gaps gave enough room for Bosnia to declare its independence from Yugoslavia. Then, four years passed along with an estimated 90,000-300,000 people, as cited by The Atlantic. (The variation is due to controversy surrounding the definition of a war death-toll. The lower numbers do not include indirect deaths, like death by starvation from conditions resulting from the war.)

War and death happen every day, but the United Nations classified the organized violence—ranging from concentration camps to rape—between Serbians, Bosnians, Muslims and Croats as the absolute worst human rights violation: genocide.

In Article 2 of the “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the U.N. defined genocide as an act committed “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, the Serbs are a national group characterized by its Eastern Orthodox Christian identity. The Bosniaks are an ethnic group also called Bosnian Muslims.

During the summer of 1995, in the small mountain town of Srebrenica, Bosnia, Bosnian Serbs massacred 7,000 Bosniak men, as cited by Encyclopaedia Britannica. This was just one instance of the violence.

None of the foreign or domestic dignitaries at the negotiation table in Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, selected for its distance from national attention, claimed the Dayton Peace Accords established a perfect peace when it was agreed upon Nov. 21, 1995, nor did Clinton make the claim 20 years later. But it was enough of a compromise for the presidents of Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia to sign it, to stop the violence.

Clinton recalled the Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic telling him, “This is not a just agreement, but it is more just than the war,” before finalizing what was officiated as the “general framework agreement for peace.”

This general framework formally established Bosnia as a sovereign entity and a republic for the Serbs, the Republika Srpska, as another with a united tripartisan capital city, Sarajevo. Bosnia would also become the only country in the world to be led by a tripartite presidency. Article X of the document stated, “The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina recognize each other as sovereign independent States within their international borders. Further aspects of their mutual recognition will be subject to subsequent discussions.”

It is the word “subsequent” that Clinton called “an excuse to keep anything from happening [in Bosnia].”

“We’re all sitting around here today thinking about what could be done to break the impasse,” he continued. “It is clear that if we want a successful Bosnia-Herzegovina, as a single, stable, prosperous democracy, there will have to be continued economic and political reforms, the reduction of corruption, the increase of genuine broad-based economic opportunity.”

Clinton told the audience he received a call earlier that day from the two U.S. senators who accompanied him to Srebrenica.

The senators told Clinton they were introducing a bipartisan bill to establish a U.S.-Bosnian enterprise fund to draw more private investors to small and medium-sized businesses there.

According to the Nov. 19 official congressional transcript of the bill’s introduction, one of the two senators, Rep. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), pointed to the economic scars of the war that won’t fade in Bosnia: “Per capita income in Bosnia and Herzegovina averages less than $5,000 annually. And that is a shame 20 years after the Dayton Accords. Compare this $5,000-a-year per capita to $13,000 a year right across the border in neighboring Croatia. The unemployment rate stands at 40 percent.”

Tomislav Vidovic, a Bosnian citizen, cited unemployment as the biggest challenge the state faces today. He’s also one of the three students at the University of Dayton who call Bosnia home.

The Dayton Peace Accords fellows, the students from Bosnia studying at the University of Dayton this year, led a panel discussion Nov. 9. During that discussion, Dzeneta Begic, one of the fellows, explained the difficulty moving forward in her country.

“We have beautiful places to live and beautiful places to go to and tourism, but so much ethnic tension,” Begic said. “I don’t want that [the terror of the war] to happen again or to my children … I’ve worked on a lot of projects back home that aim to maintain peace … and I feel like every time I try and do something, nothing happens. That’s what hurts me.”

I’ve worked on a lot of projects back home that aim to maintain peace … and I feel like every time I try and do something, nothing happens. That’s what hurts me.

Clinton explained that this continued conflict is why not only Bosnia, but also the United States and the rest of the world need to practice proactive politics. Politicians and citizens alike. Despite the ending of the war, there is still violence in Bosnia. There is still racial tension between white police officers and African-American citizens in the United States. There is still suffering in Syria.

“You have to make something good happen. You can’t just stop bad things from happening,” Clinton said. “That is the lesson of all these disturbances in our cities in America. That is the lesson of all these troubles we’re having in the world.”

University of Dayton Interim Provost Paul Benson said in an interview with Flyer News that the presence of the Dayton Peace Accords fellows is one way the university plans on keeping the connection between Dayton and Bosnia active. He referenced the start-up opportunities in the region for entrepreneurs from the university as another connection between the two places. Then, he shifted attention away from the university.

“But honestly, it’s just as important, I think, for the city of Dayton to celebrate one of the most influential things that Dayton has done recently in world history—to give Dayton a shot in the arm, to help us remember that we’re in a place of global importance,” Benson said. “The rest of the world looks at us that way. It’s important that we think about ourselves in that light.”

Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley laid out some of the steps the city is taking to make sure Dayton remains “a place of global importance.”

“I think for us, with the relationship Dayton has with Bosnia, we’ll continue to see how we can encourage good behavior, right.” Whaley said in an interview with Flyer News. “We’ve signed an MoU [a memorandum of understanding, a formal agreement between two or more parties] with three of the cities of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the magistracy. So encouraging those three cities to work together, as well as the city of Dayton and our assets, I think is key.”

However, Benson and Whaley have power to take action in ways ordinary citizens cannot. As Clinton said, “Most of us are not in government. Most of us have no control over national security decisions or even local police forces.”

But, Clinton stressed that doesn’t mean citizens don’t have responsibility to increase instances of good in the world.

“We still are citizens in the battle for an inclusive future. Inclusive economics. Inclusive politics. Inclusive societies,” he stated. “And winning, over the long run, depends upon not just stopping bad things from happening or even holding the people who do bad things accountable. We also have to make good things happen.”

Editor’s note: All references to Bosnia after the first mention of Bosnia-Herzegovina refer to the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Graphic by Amanda Dee, photos by Multimedia Editor Chris Santucci.